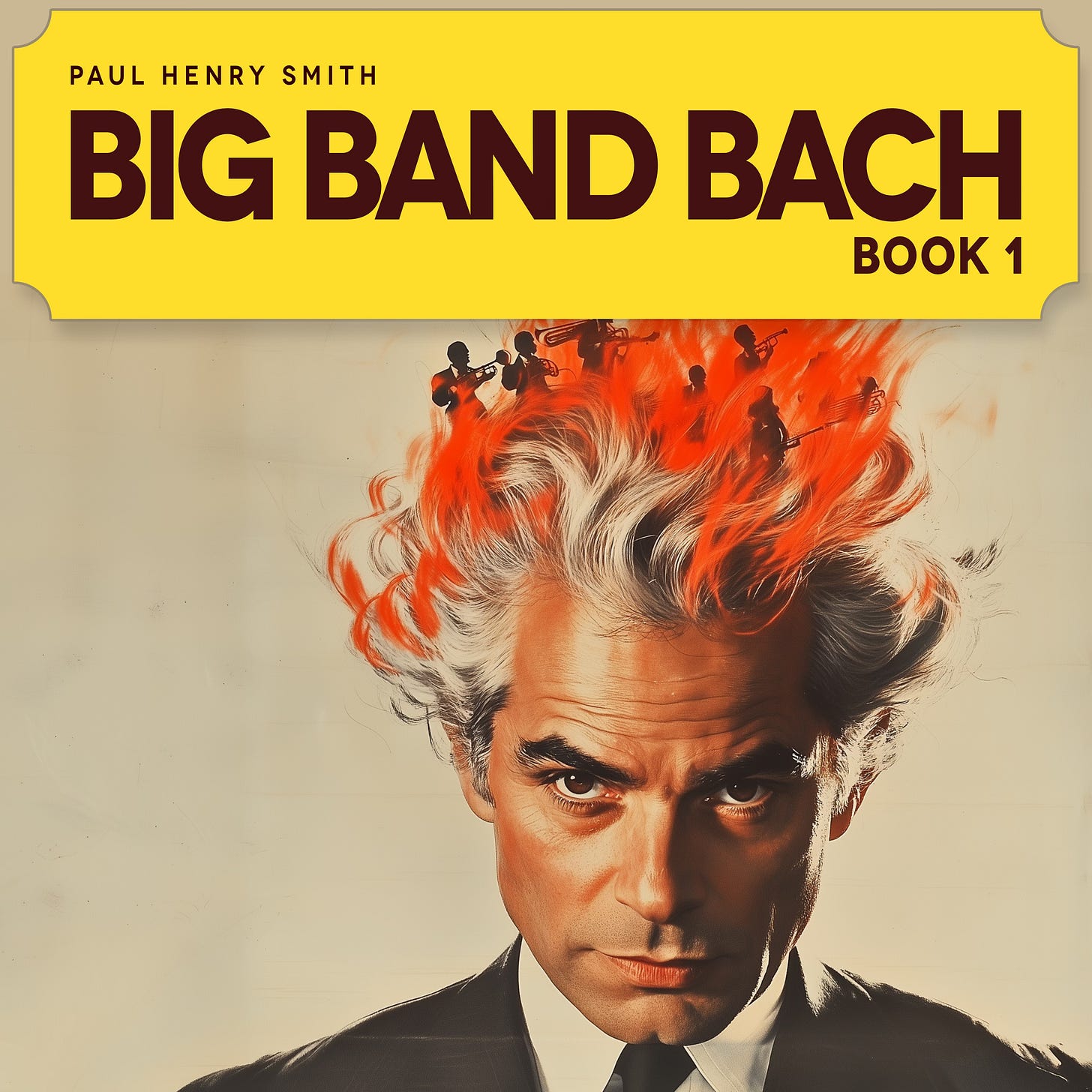

Check out the big band-style version of the entire Bach Well-tempered Clavier, Book 1 on your favorite streaming service.

Today, we’re exploring a groundbreaking experiment where classical music and artificial intelligence intersect in a way that’s completely new. My name is Paul Smith. I began my career in classical music, studying with Leonard Bernstein, attending Curtis, and conducting orchestras. I also worked on music technology at MIT, where I used the NeXT machine to play an actual grand piano and conducted the first live Beethoven symphony with a digital orchestra. This experience puts me in a good position to evaluate an interesting new AI capability in music.

We’ve all seen the buzz around generative AI in fields like art, writing, video, speech, code, and even music. Most of us approach these tools like slot machines: pull the lever, see what comes out. It’s fun, but if you’re not an expert, you might not notice the flaws. So, where does music fit into this? While imperfect output isn’t catastrophic in casual use, for those of us who think in music—people for whom music is an entire form of intelligence—it’s a different matter.

This is where Suno comes in. Think of Suno as ChatGPT, but for music generation. Unlike other music AIs, which primarily work with text prompts, Suno allows you to prompt it with a musical recording. Just as AI art generators let you refine outputs with visual prompts, Suno lets musicians guide it using music itself. This means we can now create new music by providing musical input, directly interacting with the AI in the medium of musical thought.

For my experiment, I wanted to see if Suno could go beyond mimicking notes to detect the deeper essence of my musical style. Could it interpret how I played a piece and apply that same feel to something new? To understand why this matters, let’s talk about the layers of meaning embedded in a musical score. When interpreting a piece like Bach’s Fugue No. 21 in B-flat major, the notation holds a wealth of information: harmonies that naturally build and release tension, melodies that rise and resolve, phrases that come to their natural conclusions. These aren’t subjective choices; they’re factual relationships embedded within the music, visible to a skilled reader.

Despite decades of music software, most technology misses these layers. Traditional music AI can play notes but doesn’t truly read the score. It doesn’t grasp the relationships that make music come alive. My question was simple: could Suno detect the deeper musical intelligence in my performance and respond with a new piece that preserved the same structure or energy, even in a different style?

To test this, I used my performance of Bach’s fugue as a musical prompt and asked Suno to reimagine it in a completely different style: a 1940s Vegas big band. If Suno was truly capable of interpreting musical intelligence, it might translate my phrasing and dynamics into this new genre rather than just mimic the original.

The result was surprising. Suno didn’t merely replicate the sound of my performance—it adapted it. My pauses became syncopated beats, crescendos turned into brass swells, and dynamic shifts transformed into the energy of a swinging jazz band. It wasn’t perfect, but it often captured the essence of my phrasing and dynamics in ways that felt coherent within the jazz idiom.

One moment stood out: midway through Suno’s rendition, the brass section picked up a theme and swelled with exuberance. It amplified my original crescendo into a vibrant, jazz-infused expression. This wasn’t robotic playback—it felt as though Suno had absorbed a part of my musical intent and reimagined it in its own style.

So, what does this mean for the future of music creation? Imagine an AI collaborator that doesn’t just generate generic sounds but responds to the way you play, adapting to your phrasing and energy. It could be a powerful tool for musicians to experiment with variations, hear new interpretations instantly, and explore their creative processes interactively.

For students, this could offer immediate insights into how phrasing and dynamics shape a piece, transforming how music is taught and learned. Too often, students spend years mastering the mechanics of sound production before they even begin to explore the balance of musical energy in performance. Suno offers a glimpse into a future where that exploration could start much earlier.

Of course, Suno isn’t perfect. Its output can be wildly irrelevant, requiring patience and persistence to sift through the noise. This inefficiency is a serious drawback and must improve for AI to become a reliable partner in augmenting musical expression. Still, Suno marks the beginning of a new chapter in music technology—one where AI doesn’t just generate sounds but engages with the intent within music itself. For the first time, I felt like I was in a duet with a machine that wasn’t just playing notes but was truly listening to my musical expression.

This kind of AI opens new possibilities for creativity, collaboration, and exploration in music, offering musicians a peer-like level of augmentation. If that doesn’t make Bach raise an eyebrow, I don’t know what will.

Check out “Big Band Bach” - the entire Bach Well-tempered Clavier, Book 1, on your favorite streaming service.

Copyright © 2024 by Paul Henry Smith